April 25 is World Malaria Day, dedicated to raising awareness of the disease and how to prevent it. The beautiful thing is, malaria can be eradicated and we know how to do it. It once existed in North America and Europe, where it's now all but nonexistent. More recently, a focused effort by the government to remove mosquito breeding grounds has made malaria practically extinct in Maritius, an island east of Madagascar.

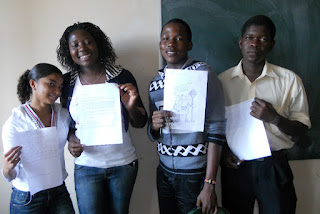

To commemorate the day, my English students made informational signs (using the imperative tense) and wrote about their experiences with malaria. I've included some of the best ones below (with some minor grammatic edits).

And for an American account of a brush with malaria, check out my blog from last July: http://pcvaleriecooper.blogspot.com/2011/07/what-statistics-cant-tell-you.html.

Use your mosquito nets kids!

Teodora, Emilia, Milton and John I was born and grew up in Mozambique and I have never been exempt from getting malaria, as any citizen of Mozambique. At 19, I had a dramatic experience with malaria, showing that to get it there's no age. It was 2 pm when I felt a headache; I went home to take parecetamol. That night I was feeling so bad with a headache, nausea, vomiting, weakness and hallucinations. My parents took me fast to the hospital. There I was treated. I started to get better the next day; I could talk and eat normally. I suffered from an illness that I could take care of. I had good luck, because my uncle had malaria and was treated within a week, but he died. The malaria that he had was cerebral malaria. After I almost died, now I prevent malaria, dreaming one day of Mozambique without malaria, such as in Texas….Working all together we can finish malaria.

- Emilia

This is a very common disease in our country, every year thousands of people get sick because of malaria. I already had malaria, in my case it was not necessary to stay in the hospital but I confess that the feeling of having the disease is not pleasant. Our bodies become brittle, usually the mouth is bitter, which makes us not want to eat.Unfortunately, my father died because of malaria. He was indifferent to the symptoms which left him so weak and the medications were ineffective. Now, more than ever to protect myself from malaria I use insecticide in the house, I keep the house and surrounding area clean and I always use a mosquito net to keep me safe while I sleep. It is always good to remember “Better safe than sorry.”

- Teodora

It started off with a dry cough, tiredness and a flu-like illness. Little did I know that I was invaded with the dreadful bacteria. The next morning a strange new setup was in me, I was shivering, sweating, vomiting and as if it wasn’t enough a terrible headache attacked me. I became weak, lost my appetite and my eyes turned yellow. Due to being alone and not quickly realizing that it was malaria, I thought of sleeping with layers of all my warmest blankets. It wasn’t comfortable enough in the blankets. I called 911 and they didn’t pick up. I never knew what happened next. A few days later I woke up in a beautiful, air-conditioned white painted room. I thought it was heaven, moreover seeing the nurses in white I thought they were angels. I asked, “Is this heaven?” One of the nurses said to me, “This is the hospital, and you were in a three-day coma because of malaria.” They later told me that they followed the link of a missed call I did to 911 and found me already in a coma.”- John (from Zimbabwe)

.jpg)

.jpg)